Credit : Nicolas Malinowski

The Khmer Rouge, Maoist-Leninist party by inspiration, occupied Cambodia in the late 1970s under the leadership of Pol Pot. Anxious to make the country economically attractive through the development of rice, the excesses of this ideology caused the deaths of 1.7 million people by the use of forced labor and arbitrary killings.

Despite the bustle of the markets, the kitchen smell that invades the streets and the laughter of young Cambodians at intersections, gloominess is palpable in Phnom Penh. City-theater of the ascent to power of the Khmer Rouge 40 years ago, the city still bares scars of the brutality of the Kampuchea regime.

Credit : Nicolas Malinowski

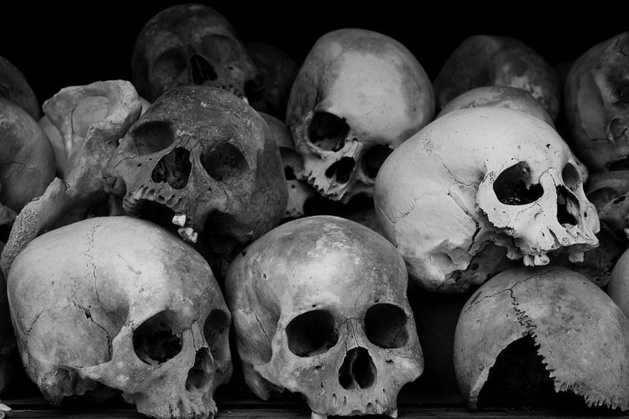

At the heart of the city one can find a high school-like building. This former place of education will never host schoolchildren in white coats ever again. In 1975, the Revolutionary Army of Kampuchea turned it into prison, the floor still bearing traces of blood. Seventeen kilometers south of Phnom Penh lies the extermination camp of Choeung Ek. Far from the humming of mopeds, silence is resounding. Here, 17,000 people died at the hands of torturers.

The murmur of a dark past resonates among the hubbub of the streets of the capital. Nevertheless, the piercing look of Cambodians seems to sink into the future without dwelling on past memories.

Besides the dead the Cambodians had to mourn, the cultural consequences of the Rouge governance are deplorable. The eradication of intellectuals who did not share their vision, seen as the first danger for totalitarian regimes, was the main ambition of supporters. After uprooting the culture of their own country, the Khmer Rouge, imposing their unique vision, destroyed the hope of an alternative perception of society. They bloodily suppressed the spirits that ventured to think differently.

After the overthrow of Kampuchea in 1979, the number of educated people has been greatly reduced. The knowledge about the genocide has only been shared in schools in 2010. The question of how and in which direction the people, whom origins are misunderstood, can go, is haunting.

A promising outward-looking economy

Credit : Nicolas Malinowski

Cambodia was quick to measure the positive impact of an attractive foreign policy. Therefore, obtaining a work visa has become commonplace. The Cambodian government facilitates trade and welcomes foreign investors with open arms. This permissive policy has paid off: since the 1990s, the country has experienced a non-stop double-digit growth. It doesn’t change the fact that 31% of the Cambodian population still lived below the poverty line in 2007, according to a UN study. Despite a ridiculously low unemployment rate, approaching 3.5%, the presence of poor workers and the unequal distribution of wealth are deplorable.

The Cambodian society is still suffering from major imbalances. The Khmer Rouge left behind many orphans and traumatized citizens, who need to be reintegrated today. However, the greatest disparity lies in the gap between urban inhabitants and those in rural areas, where most Cambodians live. While poverty has been reduced by 60% in Phnom Penh, it has only been by 22% in rural areas. The government also carried out the expropriation of large tracts of agricultural land for the benefit of private entrepreneurs, leaving many farmers without land. In a country that is 85% rural, the vast majority of Cambodians are struggling to make their voices heard, in a context where the interest of the wealthy merges with that of the rulers.

The persistence and longevity of these inequalities pose an imminent threat to the recently acquired stability of Cambodian society. The regime’s balance must remain through the promotion of human rights. And Cambodia is now witnessing its progress: it has free elections, the death penalty was abolished in 1989 and defamation is no longer considered a crime. But the possibility to individually progress remains hampered by the disrepute of identity and roots of Cambodians. Today, recreating its own ferment is the first aspiration of the new generation. The fight against historical amnesia raises the Cambodian youth’s awareness and gives it every chance to dare expressing its feelings.

A gesture of remembrance

Historical commemoration is essential to national reconciliation. Non-governmental organizations replace the inadequate legal training, due to the disappearance of many intellectuals in the 1970s. 2,099 NGOs have been established in Cambodia within 10 years, according to a census conducted by the Cooperation Committee of Cambodia in 2011. Thanks to exhibitions and debates, they promote the idea of learning from the past. While certain laws suffer from a lack of transparency and readability, some NGOs such as Destination Justice seek to improve the Cambodians’ understanding of their rights. The creation of a rule of law must be done with the citizens’ awareness of their prerogatives.

Bokor forest, in southwest Cambodia, still houses rare tigers and leopards. This fact, when told by the gamekeeper, usually makes people fear of being face to face with one of these felines. But the surprise is not the one we expect. The face-to-face actually happens in large deforested areas and surrounded by resorts. No wild animals on the horizon, but concrete blocks scattered here and there, putting up with the foliage.

The government poses no limit to the investment, whether touristic, industrial, domestic or foreign. This complacency is mainly achieved at the expense of their cultural, biological and environmental heritage. The absence of architectural homogeneity reflects a breach in the deepening of reflection on urbanization policies. This is where the paradox of Cambodian society lies: how to preserve a cultural heritage and legacy without being aware of its wealth? Again, the horrors of the Khmer Rouge regime are felt. Snatching the Khmer people from its culture, Kampuchea led Cambodians to focus on the future, at the expense of understanding their roots.