“London's economy may be doing better than the rest of the country but that obscures the fact it has the highest poverty rate”, states Bharat Mehta, Trust for London chief. According to London’s Poverty Profile, a study published at the end of 2013, 28% of the London population is living below the poverty line. In other terms, 2.1 million people earn 60% less than the average income rate in the United Kingdom. Poverty does not affect the entirety of the population. It is women, people who work part-time and older workers who are suffering. These are sections of society whose situations are already precarious. The main affected sectors are retail, maintenance, hospitality and the catering industry. There has been a 23.7% wage decrease for the poorest 10% in London. As rent is increasing and benefits are decreasing, these inequalities are have huge consequences for the physical distribution of poverty in London.

A map of poverty

”, she stated to BBC1 last January. The situation in England is such that the minimum wage is below the living wage and cannot meet a person’s daily needs. According to Bennett, who discussed the subject in a debate for World Finance, insecurity is linked to overconsumption and thus lack of resources. Creating a sense of security

”, she stated to BBC1 last January. The situation in England is such that the minimum wage is below the living wage and cannot meet a person’s daily needs. According to Bennett, who discussed the subject in a debate for World Finance, insecurity is linked to overconsumption and thus lack of resources. Creating a sense of security would thus contribute to a social wellbeing and to environmental protection.

would thus contribute to a social wellbeing and to environmental protection.

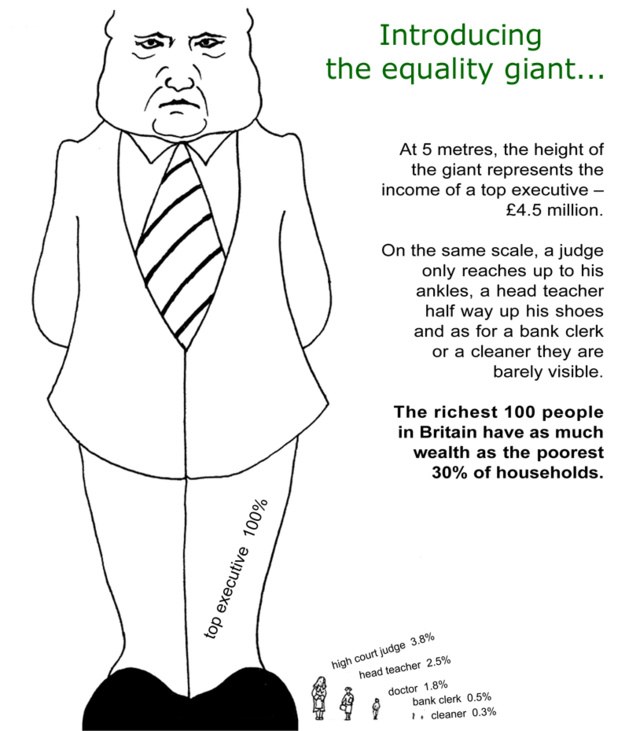

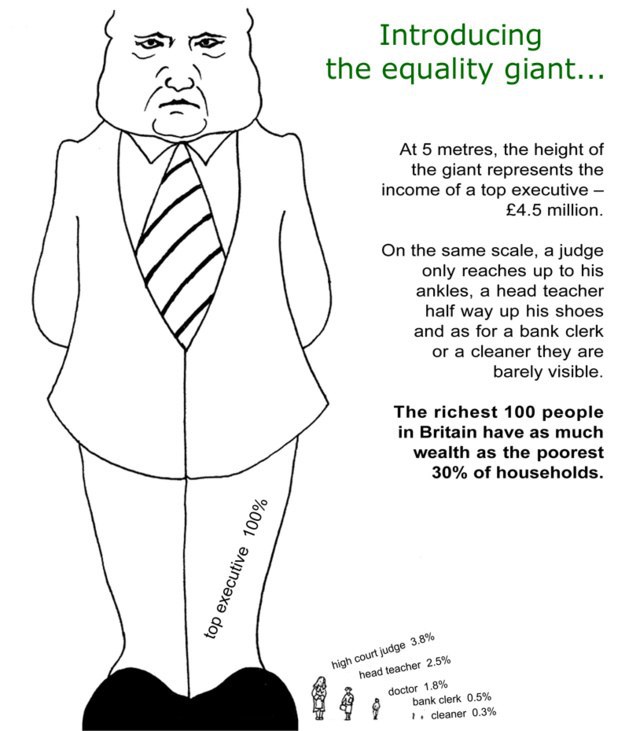

A symbolic exclamation

market, equal to 4.5 million pounds a year. In comparison, a nurse would only stand a few centimetres high. Since his debut, the giant has become the emblem of this independent organisation in their battle against poverty. Their main argument is that reducing inequality is the best way to recover from the crisis.

market, equal to 4.5 million pounds a year. In comparison, a nurse would only stand a few centimetres high. Since his debut, the giant has become the emblem of this independent organisation in their battle against poverty. Their main argument is that reducing inequality is the best way to recover from the crisis.