Credits Salomé Ietter

Fighting went on through the 80s, including the Mountain War in the Chouf District, from 1982 to 1984. Militiamen from the Phalange and Israel forces attacked the Druze, a Muslim community in the mountains. That was when Hezbollah was founded and the competition against the Amal movement started. Both parties were claiming they were Shia, and therefore became symbols to the Southern Lebanese people, protesting after they suffered the Israeli raids against the Palestinian. International Forces arrived in Beirut in 1982, but left in 1984. The United States were considered as allied to Israel, therefore opposition grew stronger upon their arrival. In April 1983, a suicide attack killed 63 people and injured many more.

Fighting went on through the 80s, including the Mountain War in the Chouf District, from 1982 to 1984. Militiamen from the Phalange and Israel forces attacked the Druze, a Muslim community in the mountains. That was when Hezbollah was founded and the competition against the Amal movement started. Both parties were claiming they were Shia, and therefore became symbols to the Southern Lebanese people, protesting after they suffered the Israeli raids against the Palestinian. International Forces arrived in Beirut in 1982, but left in 1984. The United States were considered as allied to Israel, therefore opposition grew stronger upon their arrival. In April 1983, a suicide attack killed 63 people and injured many more.

The solution was hard to find. The various groups involved disagreed on which priorities to follow in order to resolve the conflict. According to the left-wing and the Shia, what needed to be done was give up on political communitarianism and favour the unification of the country; a majority of so-called Christian parties refused to place their future in the hands of foreign armies, especially if they were Syrian. Michel Aoun became interim President in 1988, during elections that were hampered by militias.

Although the Administration wished to admit three Christians and three Muslims into the Government, the idea was rejected by the team, who created their own Government in West Beirut. Two Governments then coexisted: the one that was led by Michel Aoun and the other led by Selim al Hoss, who protested against Aoun’s separatist ideas. Instead of fulfilling his mission of electing a legitimate President, he was focusing on chasing Syrian troops away from Lebanon. On October 22nd 1989, in Taif, kings from Jordania and Saudi Arabia signed an agreement with the Algerian President, in a view to bringing back the balance of power.

In October 1989, the war was over and the Taif agreement was signed, which resulted in Syria gaining more momentum in Lebanon. The United States, thankful as it was for their support during the Gulf war, allowed Syrians to intervene in Lebanon and get rid of General Aoun. Throughout this time of near occupation, which ended in 2005, many Lebanese claimed they either supported or rejected Syria. This opposition still prevails today in political arguments, whether it is at the dinner table or during intellectual debates. During the year 1988, Dania’s father sent her and her sister to their Grandmother’s, who lived in the mountains above Beirut. Then, one month before the war officially ended, Dania remembers the day when her father took them down town for the first time since they were back. It was all destroyed, wrecked, grey, lost in the mist of war. “All I remember is that it was hideous, and I wanted to go home. I did not perceive any symbolism in it; it was only sheer destruction.”

In the centre of town stands a statue, originally in tribute to the Lebanese martyrs that were hanged during the Ottoman rule. Since 1989, it has taken a second meaning. Damaged by the war and covered with bullet holes, it is now part of a post-war symbolism, which consists in ensuring that nothing will ever fall into oblivion. As for Dania, this statue, symbolic as it is, represents above all a sinister era and the impersonates the memories of Lebanese killing each other and of a war which even today people fail to understand. The death toll rises to 150,000 and many people fled the country or were reported missing, and those who stayed were left with persistent questions. Many students and researchers take interest in that period: how the population managed to re-adapt, and also the particulars of war economy, which is a relevant question according to Dania: “The only place down town that was spared by the war is the street where all the banks are”.

She believes that the Syrian era that followed was a “remarkable” period of peace, although it still was occupation. It was marked with the Reconstruction and economic boom, emigrants came back into Lebanon, restaurants reopened, people got married. “Strangely enough, it was the most peaceful period that people from my generation ever knew”. It was also marked with dictatorial practices, with the omnipresence of Syria, which justified the Lebanese nicknaming their own country “Middle East’s prostitute”, thus adding insult to the injuries of civil war. Throughout most of its History, this beautiful nation has been invaded, directed and made to follow the interests of other players, other states or other populations.

Laughter rather than tears

On discussing those hurtful events, a new philosophy emerges. The brain’s ability to resist, to laugh rather than to cry, appears clearly in the way people talk about the war. Dania says: “One really is way stronger than one thinks they are. When you tell the story, you think: “Maybe I’m not going to survive”. But then you become another person. You directly adapt to the situation and you do survive. Only afterwards, when it’s all over, then you feel exhausted and you start having nightmares”. A psychologist who worked with Dania insists on how this conflict shows that “the Lebanese have been extremely enduring. When you get used to receiving shocks again and again on a long period, without being directly hit, you begin to gain true endurance, you learn how to adapt and you grow stronger and stronger. You understand how human-beings function, they are a very interesting self-adapting machine. You can heal yourself or make yourself sick, as long as it doesn’t concern too much of a trauma.”

“If you think you will die, then you won’t survive.”

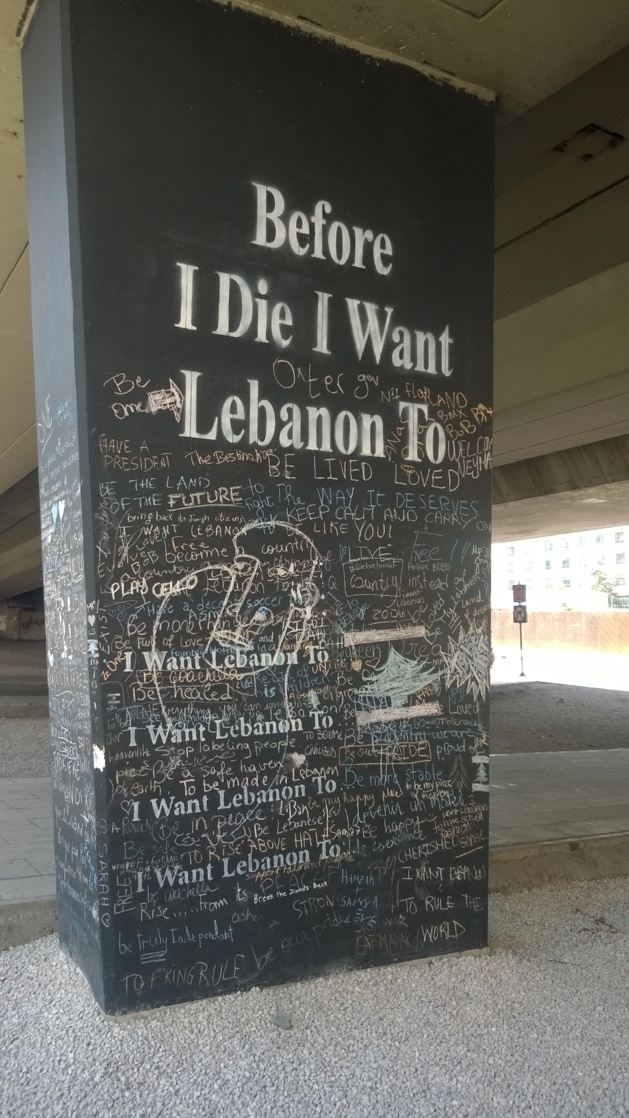

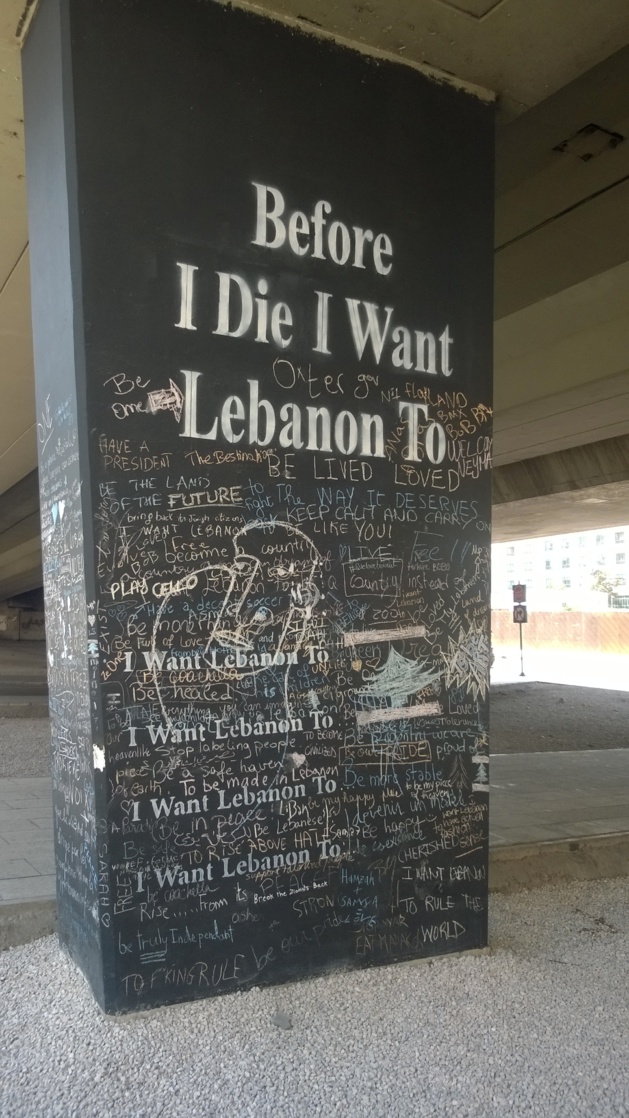

In 2012, Candy Chang, an American artist, imagined the “Before I Die“ project. Such works of art already exist in more than 70 countries in the world. Students have therefore reproduced this principle on several walls in Lebanon, as a nice way of getting citizens to join in creating the hope that the country needs for the future. Under the Fouad Chéhab Bridge, on the former green line, pillars have been turned into interactional walls, in April 2015.

The ever present idea of war

Facing those traces and memories, the Lebanese society is deep into the memory of war. Yet a new philosophy prevails, that of letting go. “We know war can happen tomorrow, but that is just the way it is, there is nothing we can do about it. So we live, we enjoy what we have got today. We still make plans for the future, we aren’t afraid.”

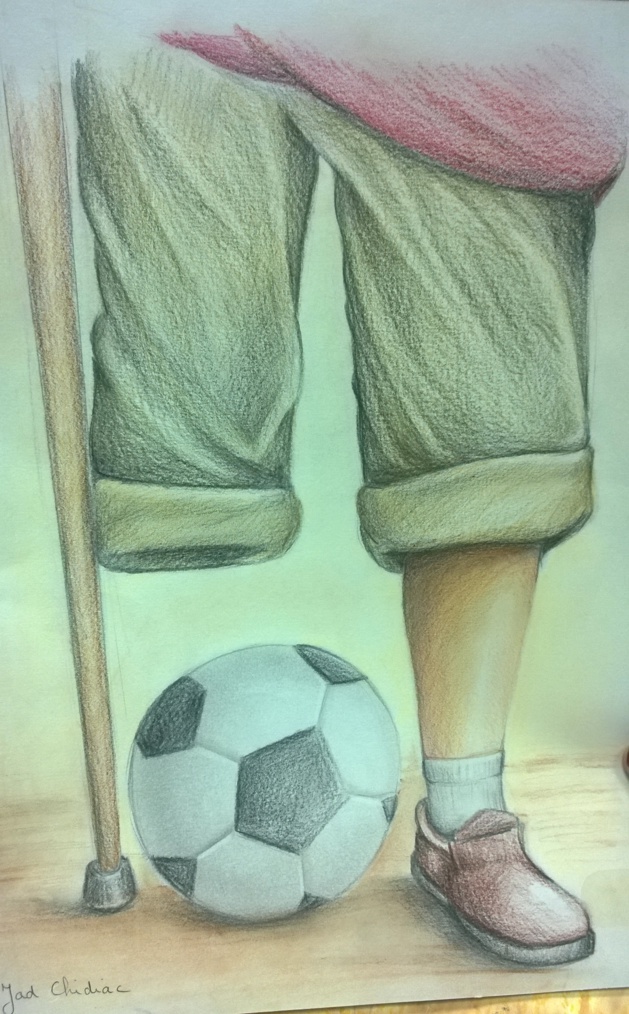

War is all the more present since it expends today towards Lebanese borders. The Syrians have been at war since 2011, and a part of them is seeking refuge in Lebanon, which causes tensions. As a children’s books illustrator, Dania remembers the conception of a leaflet telling Syrian families what to do in case of a bombing. This was all the harder for her since she has been a mother for 2 years now. “It’s been really hard for me to feel detached about it. You think you have forgotten the feelings of terror, yet they are still there, waiting for the right moment to burst out.”

Another war heritage: protest against landmines

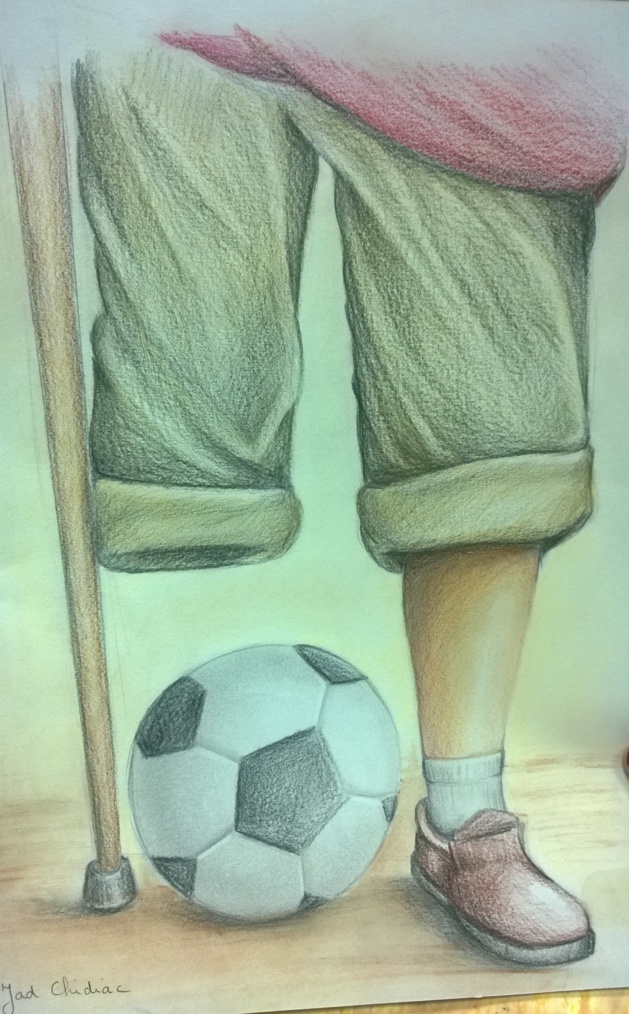

In that particular context, both the problems caused by the former wars and those caused by the current wars need to be dealt with. Concerning the struggle against landmines, it has led to many new projects in Lebanon. Along with Habbouba Aoun, the coordinator of the Land Mines Resource Centre (LMRC), Dania takes part in projects with students and children in schools in order to raise awareness on this risk.

The LMRC aims at helping those who have been affected by mines, and tries to prevent people from harm. The landmine problem is but the result of a 15-year-long Civil War followed by a 22-year-long occupation. The Centre tries to track down the mines with the UN’s help. In 2000, the approximate number was 150,000 mines, excluding the occupied zones. After these were set free, 130,000 landmines were discovered in South and West Bekaa. Israel has admitted to having put about 70,000 landmines. The aim of this project is to identify dangerous areas and report them. The socio-economic impact of their presence in the country is very important, not to mention the 2 800 victims they have injured so far. Some agricultural areas have entirely been mined, and are therefore no more cultivable. It also causes the access to services and cities to be much more complicated in some parts of the country. Since essential facilities have not been reconstructed yet, the families that were touched are even more affected.

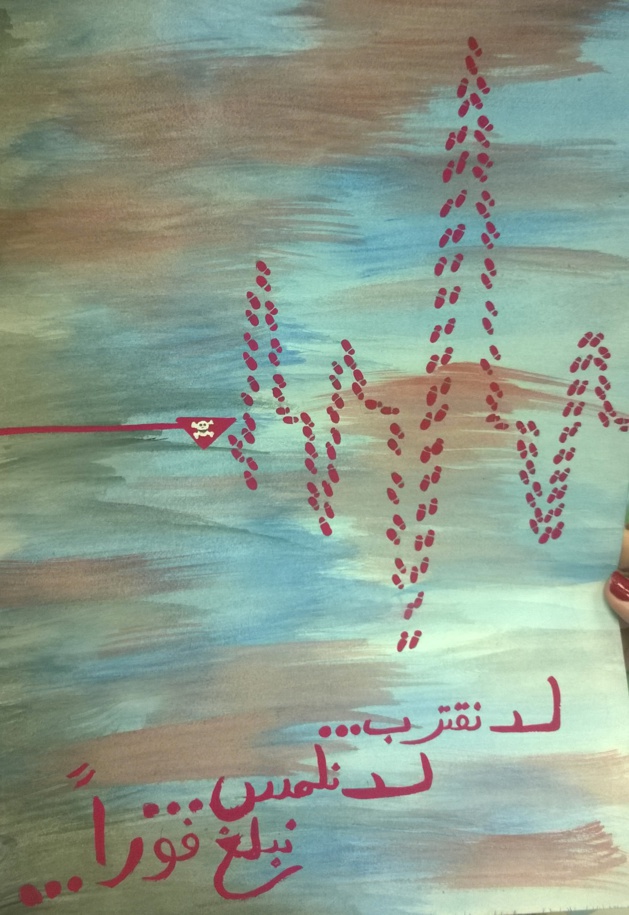

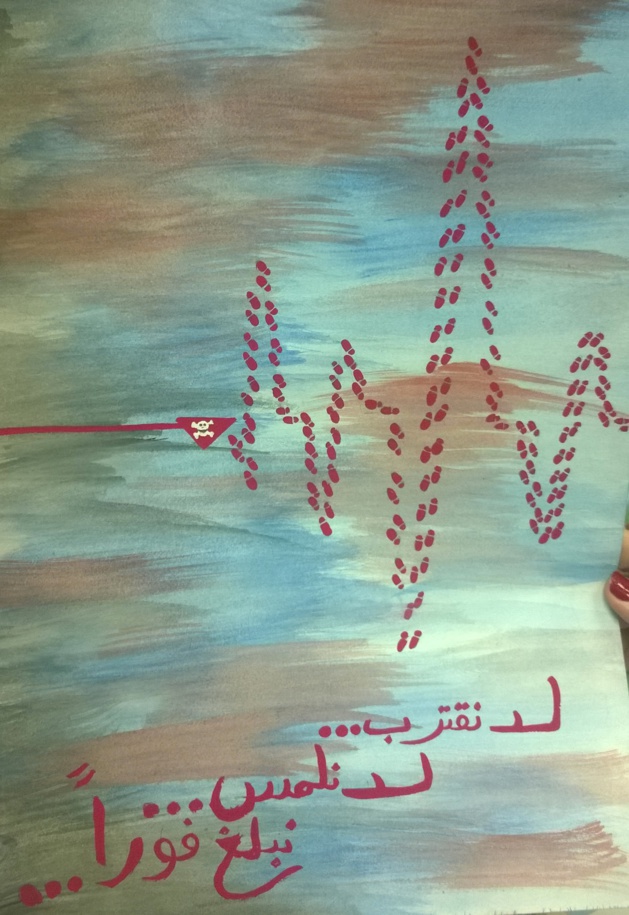

The goal is also to raise the awareness of the people who are most likely to encounter mines, and make them follow the golden rule “Do not touch, do not get close, report”. This sentence is often found on the paintings made by Beirut pupils, which Dania has selected for a inter-school contest about prevention.

What appears to some as essential memories, and that others consider as past horrors that ought to be forgotten, makes up a heritage whose influence on the country remains tremendous. Apart from the violence that is shown by visible scars, there is also something nice in the way the Lebanese remember the war: it allows us to consider it differently, to debunk its myths and understand the humanity that it can also bring out.