Photo credit : MaxPPP

Their name, Sapeurs, comes from the French slang se saper, meaning to dress with class, but also from the acronym of their social group : La Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes (the Society of Ambianceurs and Elegant Persons). La Sape can be traced back to the early years of colonialism. The French had set out to civilize African people by providing them with European second hand clothes as a bargaining tool to gain the devotion of the superiors. Although war and strife have damaged the Congo over the years, there has been a revival of La Sape in Brazzaville, the capital of the Republic of Congo. Despite campaigns taking place prompting the barring of the subculture from public spaces, they are now well respected, representing stability and tranquillity amidst the turmoil in the country. According to powerful government minister for specialised economic zones, Alain Akouala Atipault, la Sape indicates that the nation is returning to life after years of civil war, representing a sign of better things. Violence and fighting are characteristics that simply do not correspond with the moral conduct of the Sapeurs. Their exuberant flamboyance serves as a lighting rod for the Congolese disenfranchised youth, guiding it away from Third World Status to a modern cosmopolitanism.

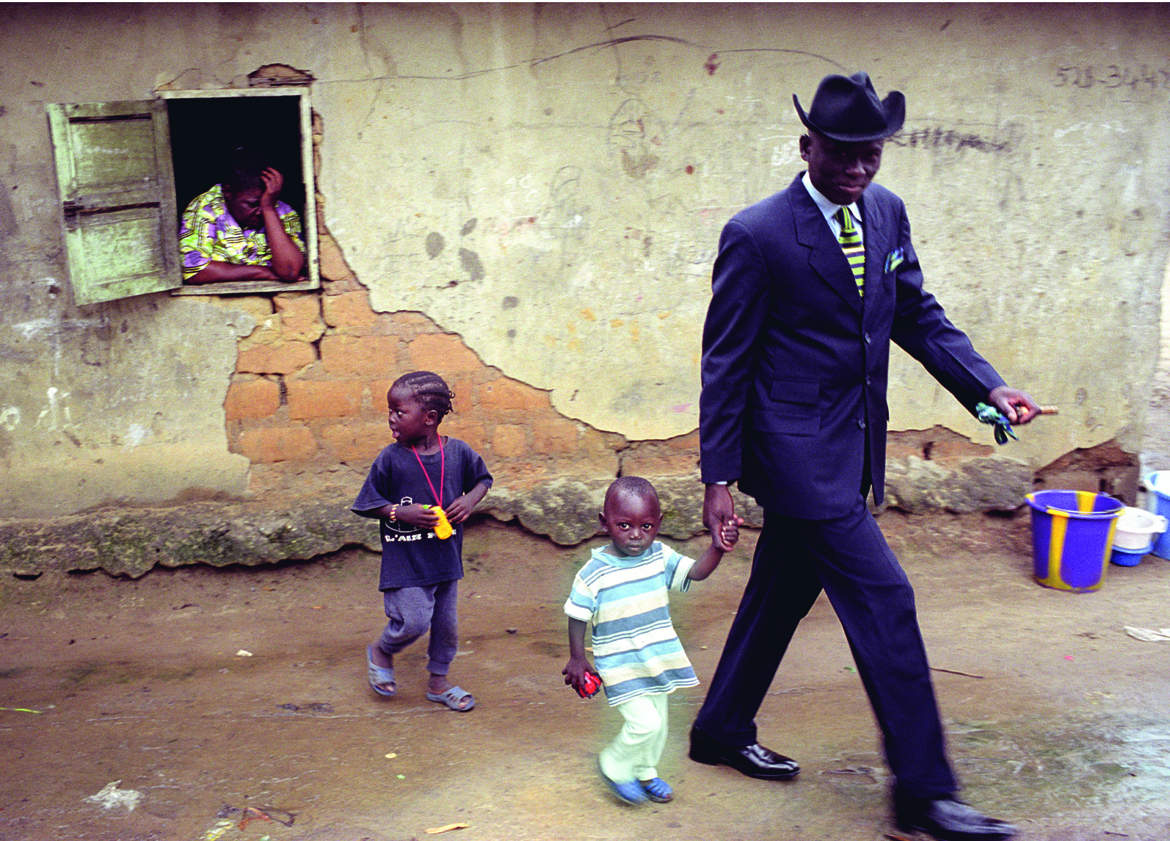

Despite their expensive attire, they are not rich men. The Sapeurs are the ordinary, democratic, working men of Brazzaville ; taxi-drivers, farmers, carpenters, cultivating the idea of beauty in their own persons, through their conspicuous dress, as part of a complex political and cultural manoeuvre. Although there has been a long history of dandies in the Congo following the slave trade and French and Belgian rule, the social movement as we know it today was revived in the 1970s by musician Papa Wemba, in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. He promoted la Sape culture, placing a heavy emphasis on the smart dress of all Congolese men, regardless of their social differences.

An ethos centred around respect, peace, integrity and honour accompanies the wardrobe of la Sape. This holds that a Sapeur has to be non-violent, well mannered and an inspiration through their attitude and behaviour. Wemba used this with a political motive. It gave birth to a wave of popular resistance to President Mobutu Sese Seko’s regime of “authenticity”, which prescribed a condemnation of symbolic ties with the coloniser and a return to traditionalism, following the recently regained independence. Wemba made use of la Sape’s culture of extravagant dress to challenge the strict dress codes which outlawed European and Western styles, imposed by the government.

Although the phenomenon is inspirational and captivating at first sight, it also has a dark side. Whilst making enough money to eat is the priority for most of the citizens of the nation, gathering enough money to acquire the perfect French or Italian designer hat to match the shoes is the priority for a Sapeur. Given the extreme poverty of the shantytowns in which the Sapeurs live, it is worrying that fashion prevails over the generally accepted basic human needs. Furthermore, the Sapeurs praise themselves on their ability to wash and stay clean and hygienic in a country where water is in short supply. What started off as a political movement has resulted in an obsession for these men, who go to extreme lengths in order to sustain their elegant taste in fashion. In their struggling Central African nation, the Sapeurs sacrifice the chance of moving to a better home, buying a car or even paying the tuitions to send their children to school. Many have resorted to illegal means to obtain their attire and some have spent time behind bars.

In a country devastated by civil wars, bombings, poverty and deprivation, against a backdrop of shantytowns, this fascinating Congolese subculture raises a dilemma. While at first glance, la Sape is a cult of the cloth, it is a revolutionary movement, which once defied political leaders, using appearance and propriety as a form of rebellion against the brutal aspects of Congolese life and generating a peaceful environment that follows them around. Yet, when we see the lengths these dedicated followers of fashion go to in order to acquire their European suits, ties, and their Cuban cigars, the fascination of the illogicality of the subculture’s lifestyle suddenly becomes more of a concern than wonderment.

The contradiction between the sophistication and style that make a Sapeur and the poor conditions of living are shown as a clash of worlds. Despite the great sacrifices made to achieve their appearance, dressing up in such refined and tasteful attire, ironically, is a way for the working men to escape and forget poverty. Within their local communities, they are a source of inspiration and positivity through conversation, dance and friendly competition, which according to the Gross National Happiness indicator represents a better way of life. Furthermore, the Sapeurs are aware of their contrasting priorities, which they defend by arguing that "a Congolese Sapeur is a happy man even if he does not eat, because wearing proper clothes feeds the soul and gives pleasure to the body". When we observe the overwhelming harmony that surrounds this cult of elegance trapped in an environment of misery, we question whether they would be violent people had their clothing not generated a sense of peace ?