Crédit Ben Curtis/AP

North Africa has always had a role as an interface between the Sahel and Europe, but today, relegated to the margin of the West in this “Third World” of such vague outlines, it seemed enclosed within itself, abandoning its relations with Sahel, determined to think that its opportunity was elsewhere, farther in the North. With the fading of the caravan trade routes due to the colonial stranglehold, the Sahara found itself landlocked, seemingly condemned to a culture of subsistence. However, immigration continued progressively and the situation began to change massively, revitalizing the whole region.

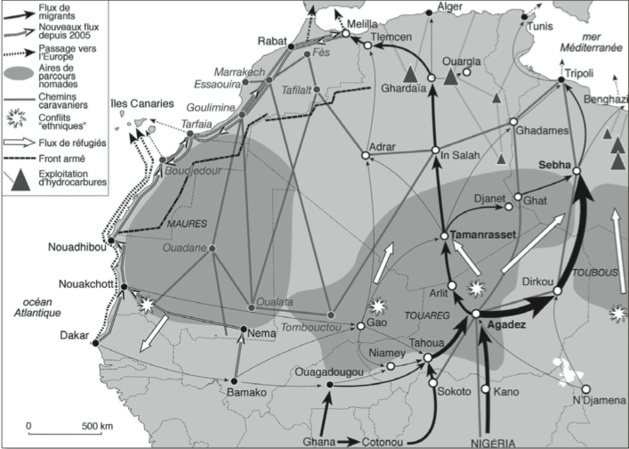

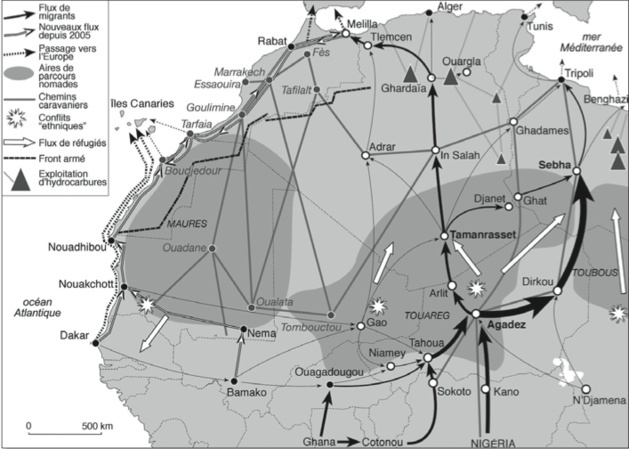

Even though originally it concerned only the traditional temporary migration of the population from the south looking for jobs in Maghreb, the increasingly strict European policies on migration made of the Sahara an “attractive” zone for “passing” candidates, making it larger and truly “trans-Saharan”. This affluence brought old roads up to date, created new ones, and was a source of an intensive urbanisation of long transit routes, transforming villages into vital nodal points for a new kind of commerce.

Cities such as Tamanrasset, Agadez or Nouadhibou, administrative headquarters and sideline villages saw their populations more than double and become cosmopolitan cities and flourishing centers of exchange. Additionally, modest relay points, border stations or simple junctions of tarmacked roads sprung up in the image of Dirkou, Nigeria, all participating in this increasingly developed social and commercial network. The result was the development of veritable exchange points in the neighboring capitals like the souk libya in Karthoum.

Due to the family and communitarian network it establishes, migration is an inescapable aspect of the establishment of an ethnic commerce : “an ant commerce”, surpassing borders, founded on the increasing importance of immigrant populations in the urban centers. Informal negotiators, they profit from regional disparities, and set up merchant routes which are strictly speaking international, but above all, alternative. Their knowledge of the “open” roads via the hold of the State, of the different needs the regions they have crossed, but also the contacts established throughout the journey make them the primary interlocuteurs. The “Ladha trafic”, from the name of the powder milk subsidized by the Algerian State and sold illegally throughout the Sahara in the 90’s or the tissue industry still going on nowadays, in which Burkina-Faso and Nigeria in Gaya became the turning tables, is emblematic of these type of semi-licit exchanges. The “Goodbye France” or used clothes represent a reverse flow which is as little-known as it is vital in the supply of clothing, and in the general life of these populations.

Therefore, it would be simplistic to think that the “transit economy” is based only on the monetization of the clandestine itinerary, even if it is evidently a non-negligible resource for the local population. It consists mostly of a human regionalization by the base of the Sahara, by the development of these new poles of urbanisation, as much as a point of exchange. Transitional cities dedicated entirely to the trade going through them represent an alternative structure of the territory. They are, as Olivier Pliez calls them, Saharatowns, hybrid entities, way stations of state presence and the foundation of transborder commerces.

Fluid, reversible and temporary migratory flux, but anchored in the territories

The denouncement of the clandestine immigration as human traffic has hidden the fact that it’s an exceptional organizational method. Contrary to the structured and hierarchized mafia network, strangers to their environments, most travels and itineraries are made by local populations or migrants themselves. In fact, these require more than a “simple” crossing through state borders and bypass of police surveillance, getting through symbolic and identity limits from inside and outside each society. The “passer” is first of all a mediator between the migrant and the new social environment.

Therefore, the clandestine route only rarely knows a form of institutionalization and is mostly presented as an irregular mesh of passer’s network, interchanging in each new environment and most of all, not accomplishing themselves in one time. There are numerous obstacles, because of the time it takes to reconstruct a nest-egg, especially in endowing itself the function of the “passer” by highlighting the fact they know how to travel. It’s a step by step immigration that can take several years to happen. In 2007, the average time a clandestine migrant spent in Morocco was estimated to be two and a half years. In the same way, because of control hardness, the latter establishes more and more in the country of transit, invalidating the idea of a massif exodus to Europe. In 1999, 9 out of 10 refugees from the Democratic Republic of Congo stayed in Africa. Hein de Haas estimated to more than 100.000 people the population that immigrated to Algeria.

Thus, the migrant’s route only seems possible by its superposition to the local preexisting circulations, in other words, by the existence of a certain solidarity and cooperation. Mixed marriages and the existence of an ethnic commerce are the material embodiment of this. These things reveal that immigration is more than a simple lucrative traffic, and that it embodies a certain communion of the peripheries against the central powers. Even if since the 2000’s the majority of migrants are transnationals, more precisely, sub-Saharans, most of the residing populations in these states are originally migrants. Not only the European dream, but most of all the forced settlement of the nomads, the massive exodus toward cities constitutes an internal migration, marginalized within urban centers as a result of a lack of infrastructure and contempt.

It isn’t surprising to note that the establishment of immigrant groups and the marking of their route takes place in landlocked and disadvantaged regions and sections. It’s the Touaregs and Toubous in the desert, and in the oasis’ of Mali and Nigeria, Rif’s old autonomist populations at the Morocco-Algerian border, or even the Hartani, as ancient slaves living in communal sectors. Migratory flux thus represents contested places and the removal of state authority, becoming the expression of the irredentism of these minorities.