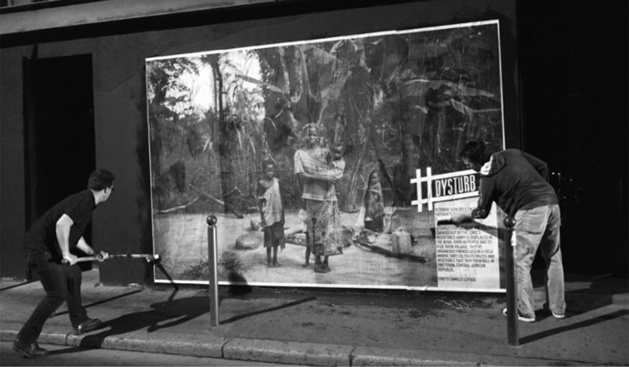

Credit Dysturb

#Dysturb is a project supported by a vast network of professionals who look for an alternative to the crisis which has, for some time, affected photojournalism. The situation has also been aggravated by the crisis in the press, which is cutting its photo budget and reducing its requests. It is, in fact, a race to the image banks, with competition from a continual flow of photos from amateurs and professionals, taken by the media from the Internet and from social networks, often at low prices. This again shows the place given to low cost research, in spite of the quality of the informational content.

The crisis of photojournalism

Thus, reporters receive less and less orders, and payment which doesn’t always cover the risks incurred on the job.

What remains is frustration; the frustration of a photographer who, after having spent several months on the ground, often risking their life in difficult situations, cannot truly recount what they have seen, cannot make visible the stories of which they have been witness. On a job lasting several months, for example, only some prints will manage to find their place in the press; the others won’t see the light of day due to the lack of vendors, or simply a lack of means.

What remains is frustration; the frustration of a photographer who, after having spent several months on the ground, often risking their life in difficult situations, cannot truly recount what they have seen, cannot make visible the stories of which they have been witness. On a job lasting several months, for example, only some prints will manage to find their place in the press; the others won’t see the light of day due to the lack of vendors, or simply a lack of means.

The response of #Dysturb

Launched by Terdjman and Girette last February, #Dysturb was therefore born of a common desire to make their account visible, and that of other reporters, to tell and inform the nation of the realities often very quickly forgotten by the media. To do it, they decided to bypass the required visit to the mass media, putting up their testimony directly in the street, ‘the biggest social network in the world,’ according to Terdjman.

So they go out at night, in groups and armed with glue, in order to cover the towns with giant photo prints, taken on all four corners of the globe. The 4x3 prints thus become, by the light of day, windows onto the world, revealing the displaced in Bangladesh, the demonstrators in Egypt, Hong Kong or Ukraine, the conflicts in Central Africa, in Gaza, in Mali, etc.

The project, financed entirely by the founders and their community, has already reached cities such as Paris, Perpignan (as part of the event ‘Visa pour l’image’), Sarajevo, and New York last October, but this is only the beginning.

The project, financed entirely by the founders and their community, has already reached cities such as Paris, Perpignan (as part of the event ‘Visa pour l’image’), Sarajevo, and New York last October, but this is only the beginning.

Terjman, who has been a photographer for the agency Gamma since 2007, is a French photojournalist who regularly travels for Paris Match, The New York Times, Geo Magazine and Newsweek. From the post-election violence in Kenya to the Russo-Georgian conflict, from Afghanistan to the earthquake in Haïti and the Arab Spring, Terdjman has been witness to numerous conflict zones and violence around the world. In a short interview, he explains the origins of the project and his view on photojournalism today.

Interview with Pierre Terdjman

Credit Dysturb

How did you become a photographer and what drew you towards photojournalism?

I started with photography in Israel, while I was in training for the newspaper Haaretz from 2002 until 2007. After having covered the Intifada for several years, I returned to France in 2007 and joined Gamma.

I’ve always wanted to discover the world and understand how people live in times of war; loving photography and having a desire to travel, I became a photo journalist.

I started with photography in Israel, while I was in training for the newspaper Haaretz from 2002 until 2007. After having covered the Intifada for several years, I returned to France in 2007 and joined Gamma.

I’ve always wanted to discover the world and understand how people live in times of war; loving photography and having a desire to travel, I became a photo journalist.

How was the idea for the project #Dysturb born? What was your goal? Who did you want to reach?

#Dysturb was born of a desire to share the news and subjects that we cover as photojournalists with the largest number of people. Tired of a lack of visibility in the traditional press and conscious of a need for change, we created Dysturb with Benjamin (Girette) in March of last year.

The aim is always to crudely stick up photojournalism to draw people’s attention to what is happening around them. Like the publicity that you see everywhere in the street, we decided to stick! That is to say, we never vandalise and we use a water-based glue.

#Dysturb was born of a desire to share the news and subjects that we cover as photojournalists with the largest number of people. Tired of a lack of visibility in the traditional press and conscious of a need for change, we created Dysturb with Benjamin (Girette) in March of last year.

The aim is always to crudely stick up photojournalism to draw people’s attention to what is happening around them. Like the publicity that you see everywhere in the street, we decided to stick! That is to say, we never vandalise and we use a water-based glue.

How do you choose the photos and the places to stick them?

We choose the photos according to the news. We have a network of photojournalists that we know, and alongside that we constantly research new subjects.

Have you had difficulty whilst carrying out the project?

We are looking for money to be able to continue the project, which until now has only been financed by ourselves.

We choose the photos according to the news. We have a network of photojournalists that we know, and alongside that we constantly research new subjects.

Have you had difficulty whilst carrying out the project?

We are looking for money to be able to continue the project, which until now has only been financed by ourselves.

Credit Dysturb

Dysturb translates as ‘disturb’ in French. Has the project given rise to the desired reactions and impact?

In fact, the idea was to disturb people and to put them face to face with the world in which they live. We did it: people reacted and even in Paris people asked us to come stick photos on their wall or in their neighbourhood.

In fact, the idea was to disturb people and to put them face to face with the world in which they live. We did it: people reacted and even in Paris people asked us to come stick photos on their wall or in their neighbourhood.

You’ve chosen the road as your exhibition venue. What motivated this choice? Because aren’t the works stuck in the street condemned to disappear in the short term, under the weight of change in the city?

Using an urban space was the best way to reach the biggest amount of people possible. The street is still the biggest social network in the world. For artists or people like us, the message can be very strong. All day, we consume publicity in the street, we are sold another thing! In fact we don’t sell anything, we offer people the possibility to enquire for free, to become aware of what is happening around them.

Using an urban space was the best way to reach the biggest amount of people possible. The street is still the biggest social network in the world. For artists or people like us, the message can be very strong. All day, we consume publicity in the street, we are sold another thing! In fact we don’t sell anything, we offer people the possibility to enquire for free, to become aware of what is happening around them.

What role do you grant to social networks? What do you think, more specifically, of Instagram and Twitter?

Naturally, we are on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook, etc. For us it’s very important to make our community grow and to let people know what it is that we do.

Naturally, we are on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook, etc. For us it’s very important to make our community grow and to let people know what it is that we do.

In a world that is more and more saturated with images and information, where even the attention of the public is fragmented, many subjects/reports struggle to find the right visibility. What do you think of this ‘competition’ of information, and what do you think would be the most conceivable solutions?

Frankly, we are just trying to create an alternative. No more crying over our profession which is going badly; today with Dysturb, we are looking for solutions. A photo of Johnny is going to be more interesting than a photo of Iraq for a magazine that wants to sell copies. It’s the reality; it’s also true that people no longer want to learn. They no longer believe everything they are told.

Frankly, we are just trying to create an alternative. No more crying over our profession which is going badly; today with Dysturb, we are looking for solutions. A photo of Johnny is going to be more interesting than a photo of Iraq for a magazine that wants to sell copies. It’s the reality; it’s also true that people no longer want to learn. They no longer believe everything they are told.

What place does photojournalism have in this dynamic and what should its role in society be today?

The aim of photojournalism is to inform people and to make them discover subjects they didn’t previously know about. That’s the role of the photojournalist, to raise the alarm about unknown issues.

Often, photojournalists are compared to anthropologists. In this respect, what do you think of the position of the photojournalist? Do they maintain a real objectivity, given that each photograph is the result of a choice (subject, composition, etc) that can be subjective?

Objectivity is a word which should be banned from the language of the journalism schools; I prefer intellectual honesty in the way of treating a subject, respect for the subject and above all for the people. Respect and sensitivity are essential.

The aim of photojournalism is to inform people and to make them discover subjects they didn’t previously know about. That’s the role of the photojournalist, to raise the alarm about unknown issues.

Often, photojournalists are compared to anthropologists. In this respect, what do you think of the position of the photojournalist? Do they maintain a real objectivity, given that each photograph is the result of a choice (subject, composition, etc) that can be subjective?

Objectivity is a word which should be banned from the language of the journalism schools; I prefer intellectual honesty in the way of treating a subject, respect for the subject and above all for the people. Respect and sensitivity are essential.

What is it that guides and drives you as someone who risks your life in often quite dramatic situations?

Telling the story of those who can’t.

Has there been a moment during your career when you’ve thought that it’s not worth it (putting your life in danger)?

Yes that’s happened, but it passes very quickly!

Telling the story of those who can’t.

Has there been a moment during your career when you’ve thought that it’s not worth it (putting your life in danger)?

Yes that’s happened, but it passes very quickly!

You’ve travelled a lot and photographed different revolts, different people, and different realities: have you found one, or several, common points between the different contexts?

Poverty, lack of education, deprivation of liberty and freedom of speech are those that you see the most frequently in countries in conflict, I think.

Among your projects and trips, can you tell us of a memory, a story that has affected you and that is close to your heart?

My last assignment in Central Africa. Without a doubt the most violent and intense place that I’ve been able to see in these last years.

Poverty, lack of education, deprivation of liberty and freedom of speech are those that you see the most frequently in countries in conflict, I think.

Among your projects and trips, can you tell us of a memory, a story that has affected you and that is close to your heart?

My last assignment in Central Africa. Without a doubt the most violent and intense place that I’ve been able to see in these last years.

If you could change one thing in the world, what would you change?

If I could change one thing in the world? I have no idea, there would be too many things to change, wouldn’t there?

Autumn is already here and winter is approaching. What are your projects for the New Year?

Soon after Perpignan, Bayeux and New York, we’ll go to cover Belgium, Holland and other countries. And then I also hope to return to taking photos, one of these days!

If I could change one thing in the world? I have no idea, there would be too many things to change, wouldn’t there?

Autumn is already here and winter is approaching. What are your projects for the New Year?

Soon after Perpignan, Bayeux and New York, we’ll go to cover Belgium, Holland and other countries. And then I also hope to return to taking photos, one of these days!

Return to the street

Credit Dysturb

Vandalism for some, a form of street art or marketing for others, resorting to the street nevertheless remains a good means for visibility and expression. It reflects a need to inform and to interact with the population that is stronger than commercial logic.

The group #Dysturb aims to give a new visibility to photojournalism, and to make it more accessible to all. But, as the name indicates, it also seeks to ‘disturb’ and stir up public debate, in order to penetrate the widespread feeling of indifference that seems to emerge regarding certain themes.

The group #Dysturb aims to give a new visibility to photojournalism, and to make it more accessible to all. But, as the name indicates, it also seeks to ‘disturb’ and stir up public debate, in order to penetrate the widespread feeling of indifference that seems to emerge regarding certain themes.

However, one can still wonder whether this feeling of indifference hides, in reality, a genuine feeling of powerlessness on the part of the individual, who finds themselves constantly confronted by the media and realities that seem to them too far away and out of range. In this case, they fail to act not because of a lack of conscience, but more because of an attitude of ‘flight’ in reaction to what they have seen. On the basis of this argument, one could thus question this forced ‘imposition’ of images upon the individual, and its real impact on their behaviour.

Yet again, it’s enough to think about the mass of information, mainly publicity that appeals to the individual every day, to quickly realise that other images are imposed on them without their consent. And so, amidst an array of images, Terdjman chooses to show what is happening in the rest of the world.

#Dysturb perhaps also serves to remind us that closing our eyes when faced with situations which ‘disturb’ us won’t make them disappear.

#Dysturb perhaps also serves to remind us that closing our eyes when faced with situations which ‘disturb’ us won’t make them disappear.